Beyond the Bruises: Dr. Ruth Kempe's Legacy of Healing

The Lasting Impact of Dr. Ruth Kempe - Understanding the Hidden Wounds of Child Abuse

10 minute read

Child Abuse Prevention Month seeks to both raise awareness about preventing child abuse as well as honor the dedicated individuals who have worked to establish and strengthen child protection laws in the United States. While these protections may seem fundamental today, nationwide legal safeguarding of children from physical and psychological abuse is a relatively recent development in American history.

The Evolution of Child Abuse Awareness and Response

For most of America’s history the treatment of children was largely left up to a parent’s discretion, free from public scrutiny. A parent’s right to “raise their child as they see fit” was the predominant priority. However, scattered cases of egregious abuse in many areas of the country were well known. In 1860, French Forensic medical expert Auguste Ambroise Tardieu, published a paper describing the harrowing abuse and neglect of children in France, and in 1875, New York became the first state to legislate protection for children. Subsequently, child protection services progressed in the U.S. in a disjointed and inconsistent way, mostly managed by nongovernmental child protection societies. By 1956, those societies had dwindled, and most child protective services were under governmental control with woefully inadequate funding and equally insufficient response. With new technology using pathologic and radiologic evidence, mysterious injury cases were being documented all over the country. Pediatric radiologist John Caffey published a paper describing chronic subdural hematomas with curious bimodal distributions, limb fractures and unexplained ossifying periostitis of the long bones, his paper only hinting at possible parental abuse. New evidence was mounting that child abuse was widespread, and the resources currently allocated to mitigate it, insufficient (Myers 2008).

Clinical Diagnosis: Battered Child Syndrome

Doctors had been seeing injury anomalies in children for years, but were generally resistant to becoming entangled in accusations. So, it wasn’t until 1962 that a clinical diagnosis was established. It was originated by Dr. C. Henry Kempe, who in his youth barely escaped Nazi internment and was now Chairman of the pediatrics department at the University of Colorado School of Medicine in Denver. He had been noticing confounding injuries in children whose bodily damage was incongruent with the reported event. Spurred on by these mysteries, and frustrated by the absurd diagnoses such as “spontaneous subdural hematoma”, “spontaneous multiple bruising due to unexplained bleeding disorders”, and “failure to thrive of unknown etiology,” he set out to identify the true cause of these maladies by documenting cases and compiling evidence. After some time he, and four of his colleagues, labeled the condition The Battered Child Syndrome. In 1962, they courageously presented at the American Academy of Pediatrics with thousands in attendance, and published a contentious article of the same name in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

“The 1960s witnessed an explosion of interest in child abuse, and physicians played a key role in this awakening... As the medical profession became interested in child abuse, so did the media...Following publication of The Battered Child Syndrome, a trickle of writing became a torrent that continues to this day.” (Myers 2008).

This torrent of publicity transformed society’s awareness of this issue and would eventually galvanize the public to demand coordinated action.

C. Henry Kempe was one of the fortunate German Jews who was granted asylum in the U.S., pursued an education, and created a new life in America. In 1937, C. Henry Kempe emigrated to the U.S. from Germany, and eventually attended UC Berkeley. He continued to attend school even after he and the rest of his class were called up for military service. He graduated from UC School of Medicine in 1945 and completed an internship in Pediatrics. C. Henry served his 2 years of additional army service as an Assistant Virologist, and after his discharge from the military, continued training as an Assistant Resident in the Department of Pediatrics at Yale University. Fortuitous connections had aided his narrow escape during pre-war Germany, and also contributed to his later success as a German immigrant. However, one of his most fortunate connections, both personally and professionally, would prove to be the one with his soul mate and wife, Dr. Ruth Irene Svibergson.

Dr. Ruth Irene Svibergson

As tumultuous as C. Henry’s early life was, Ruth Svibergson’s was tranquil.

Born in 1921, Ruth Irene Svibergson was raised in a small tightly knit Swedish Lutheran community in Norwood, Massachusetts. Before Ruth’s birth, her parents and siblings had emigrated from an island in Sweden, bringing their self-sufficient way of life to their new home. With a few cows on a pasture, a large garden and an orchard, Ruth was free to roam in her natural surroundings, enjoying a peaceful idyllic childhood within a safe and stable community (Krugman & Korbin, 2012).

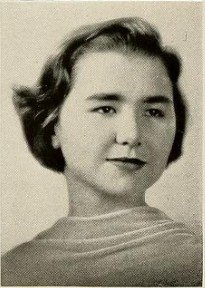

Ruth graduated from Norwood High School in 1939. Ruth was intelligent, witty, and wise-beyond her years, as seen in her yearbook quote, “Well if I don’t succeed, I have succeeded.” With this growth mindset, she embraced the idea that learning from failure can be considered a success in itself, valuing the process over the outcome.

Norwood High School. (1939). TIOT. Norwood High School.

Ruth went on to Radcliffe College, Harvard’s branch for women, graduating in 1943. Most women at this time studied nursing or teaching, but Ruth preferred to study medicine. Since Harvard Medical School did not admit women at this time, Ruth attended Yale Medical School, graduating as one of only three women in her class of 1946.

Marriage and Medicine

Ruth met C. Henry Kempe at Yale New Haven Hospital in 1948. Three months after their first date they were married.

As was customary, despite being an accomplished MD herself, Ruth’s career took a back seat to her husband’s. After both their pediatric residencies were completed, Henry accepted a position at the University of California, Berkeley. During their 8 years in California, Ruth gave birth to four daughters, becoming the primary caregiver for their growing family. After their move to Colorado, Ruth would become one of Colorado General Hospital’s first child protection team members. (CU peds 2018)

In contrast to her battle-hardened husband who was described as an intense, stern, ambitious, and unapologetic go-getter, “a steam engine at work, pushing ahead all the time and allowing no obstacle to stand in his way”, Ruth had a calm and even-tempered disposition. Described by her children as “a very loving, concerned mother who always listened, and offered quiet, sage advice”, and by colleagues as, “a lovely, charming, calm, and very knowledgeable person,”(Krugman & Korbin, 2012) Ruth was “as easygoing as Henry was energetic and driving.”(CU peds 2018) “Henry always acknowledged the importance of Ruth's input, countering her self-effacing way of minimizing her own contribution.” (Krugman & Korbin, 2012). Those who observed their professional relationship have said:

“His ally and lifelong companion, Ruth...stretched his mind and nurtured his thinking...[and may have] enticed him...to [focus on] an unrecognized, underserved population, ‘battered children.” (Kempe 2007).

As C. Henry focused on the physical side of child abuse identification and prevention, Ruth advanced her medical education by specializing in the field of child psychiatry.

“She was indispensable in Henry's work, a coworker instrumental in every aspect of his efforts. Ruth provided him and others with a valuable perspective about child development, as well as expertise concerning the emotional and psychological issues abused children face.” (Krugman & Korbin, 2012).

The Kempe Center

In 1972, C. Henry and Ruth co-founded The Kempe Center to address child maltreatment by improving the well-being of children and families, strengthening their communities, and enhancing the systems serving them through evidence-informed services, transformative research, learner-centered education, and effective advocacy.

“[Ruth] had an extraordinary understanding of how best to treat abusive parents and the children. She listened and listened and listened...she worked with hundreds of families. She was quiet and soft-spoken and developed trust with the parents.” (CU peds 2018)

Their research and advocacy at the Kempe Center would help to substantiate the need for a nationwide, coordinated, and well-funded response, resulting in the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act of 1974 (CAPTA), which continues to protect America’s children today.

Throughout the rest of their lives, Ruth and C. Henry would continue to partner in this groundbreaking work, coauthoring hundreds of seminal books, articles and lectures on the topic of child abuse. After C. Henry’s early death at age 62, Ruth would remain a member of the University of Colorado School of Medicine's pediatric and child psychiatry faculty for more than 50 years, and, in her own words, continued “...working to translate lip service into genuine action for children.”(Kempe 2007). Dr. Ruth Irene Svibergson died in 2009 at the age of 87.

“Henry Kempe would have been the first to say that he would never have accomplished even a portion of what he did in his brief lifetime without the care, support and companionship of... the "other" Dr. Kempe, Ruth Svibergson Kempe. Their relationship, with its elements of romantic love, friendship, and professional partnership, was unusually complete and their mutual dedication rare. They were truly "soul mates." (Kempe 2007).

The Kempes’ Enduring Impact on Child Welfare

As we observe child abuse prevention month, we recognize those who dedicated their lives to advancing our understanding of child abuse, leading to substantial improvements in identification, intervention, and prevention strategies. We honor Dr. Ruth S. Kempe, whose pioneering psychological research and collaborative achievements with her husband, Dr. C. Henry Kempe, transformed our awareness and response to child abuse, moving closer to a world where the physical and psychological safety of all children is a pressing priority.

We owe a profound debt of gratitude to both Drs. Ruth and C. Henry Kempe for their unwavering commitment to the health and happiness of children worldwide.

References and For Further Reading:

Caffey J. (2011). The classic: Multiple fractures in the long bones of infants suffering from chronic subdural hematoma. 1946. Clinical orthopaedics and related research, 469(3), 755–758. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-010-1666-0

Child Welfare Information Gateway. (2019). About CAPTA: A legislative history. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Children's Bureau. https://cwig-prod-prod-drupal-s3fs-us-east-1.s3.amazonaws.com/public/documents/about.pdf?VersionId=y7C6qleUR3mZJ_UJ5t_dnzCNfO6HPcPs

Guest Contributor. (2022, August 4). The Kempe Center marks 50 years of protecting the world’s children. CU Anschutz News. https://news.cuanschutz.edu/news-stories/the-kempe-center-marks-50-years-of-protecting-the-worlds-children

Kempe, A. (2007). A good knight for children: C. Henry Kempe's quest to protect the abused child. Booklocker.com. https://www.amazon.com/GOOD-KNIGHT-CHILDREN-Kempes-Protect/dp/1601452152?asin=B004RPWJTO&revisionId=8a02890b&format=3&depth=1

Kempe Center. (n.d.). About. Kempe Center. Retrieved April 8, 2025, from https://kempecenter.org/about/

Kempe, C. H., Silverman, F. N., Steele, B. F., Droegemueller, W., & Silver, H. K. (1962). The battered-child syndrome. Journal of the American Medical Association, 181(1), 17–24. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1962.03050270019004

Kempe, R. S., & Kempe, C. H. (1978). Child abuse. Harvard University Press. https://books.google.com/books?id=XZ6B-ygMMLoC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false

Krugman, R. D., & Korbin, J. E. (Eds.). (2012). C. Henry Kempe: A 50-year legacy to the field of child abuse and neglect. Springer Science & Business Media. https://books.google.com/books?id=wtr4Sf9EwmYC&pg=PA7#v=onepage&q&f=false

Labbé, J. (2005). Ambroise Tardieu: The man and his work on child maltreatment a century before Kempe. Child Abuse & Neglect, 29(4), 311–324. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/7824832_Ambroise_Tardieu_The_man_and_his_work_on_child_maltreatment_a_century_before_Kempe

Myers, J. E. B. (2008). A short history of child protection in America. Family Law Quarterly, 42(3), 449–463. https://search.issuelab.org/resources/29082/29082.pdf

Norwood High School. (1939). TIOT. Transcript Press.

Prevent Child Abuse America. (2025). Child Abuse Prevention Month 2025. Prevent Child Abuse America. Retrieved April 9, 2025, from https://preventchildabuse.org/capmonth2025/

Silver, H. K. (1980). Presentation of the Howland Award: Some observations introducing C. Henry Kempe, M.D. Pediatric Research, 14(11), 1151–1154. https://doi.org/10.1203/00006450-198011000-00001

University of Colorado Department of Pediatrics. (2018). CU Pediatrics: A history, 1930–2018. University of Colorado School of Medicine. https://medschool.cuanschutz.edu/docs/librariesprovider68/default-document-library/cu-pediatrics---a-history---1930-2018.pdf?sfvrsn=cb727fbb_2

University of Colorado. (2009, November 3). News briefs. CU Connections. https://connections.cu.edu/stories/news-briefs-0